The EU’s updated Product Liability Directive (EU 2024/2853) heralds a new era of accountability for manufacturers, especially in high-tech fields like medical devices. It expands the definition of “product” to include software and AI, making companies liable for digital features, software updates, and even cybersecurity lapses that lead to harm. The directive shifts the legal landscape in favor of patients and consumers by easing their burden of proof – courts can now presume a product was defective or caused damage in complex cases or if the manufacturer withholds evidence. It also ensures an EU-based entity is always liable by extending responsibility to importers, authorized reps, fulfilment providers, and others in the supply chain. Crucially for medical device firms, the scope of recoverable damages now includes corrupted data, and the liability “long-stop” is extended up to 25 years for latent injuries, reflecting the long-term nature of some device risks. In practical terms, manufacturers must double down on compliance (with MDR, AI Act, etc.), implement strong cybersecurity and quality controls, and maintain thorough documentation to both prevent defects and defend their products if a claim arises. At QNET, we advise clients to treat this transition as an opportunity to enhance product safety and trust. By acting now – reviewing design processes, updating protocols, supply chain agreements, and insurance coverage – companies can mitigate the heightened risks. The new PLD ultimately aims to balance innovation with consumer protection. QNET stands ready to help medical device manufacturers navigate these changes, ensuring that innovative healthcare technologies can be brought to market confidently, with robust safeguards against liability.

On 9 December 2024, the European Union’s new Product Liability Directive (PLD) – Directive (EU) 2024/2853 – came into force, marking the first major overhaul of EU product liability law since 1985. This new directive repeals and replaces the original 85/374/EEC Product Liability Directive, modernizing the rules to address the challenges of emerging technologies (like software and AI), new business models (e.g., circular economy and global supply chains), and to strengthen consumer protection. The PLD remains a strict no-fault liability regime – manufacturers are liable for damage caused by defective products irrespective of negligence. However, it introduces significant changes to ensure “better protection for victims and greater legal certainty for economic operators” in today’s digital and interconnected market.

This comprehensive overview focuses on the implications for medical device manufacturers (while noting impacts on other sectors such as software, electronics, and AI-based products). Key aspects of the new PLD – including AI and software liability, the definition of “defect”, burden of proof changes, expanded scope of liable parties, and new obligations – are explained. We also highlight specific concerns (e.g., AI’s “black box” issues, cybersecurity, proof challenges) and offer recommendations for compliance and risk mitigation under the new regime. Medical device companies, in particular, should pay close attention, as many of these changes directly affect their products and regulatory environment.

Overview of Key Changes under the 2024 PLD

- Expanded Scope to Digital Products:

The definition of “product” now expressly includes digital and intangible products such as software and AI systems (both standalone and embedded), as well as digital manufacturing files. Products that rely on related digital services (e.g., cloud-based features in a device) are also covered if they contribute to a defect. Manufacturers can be liable for defects introduced via software updates, upgrades, or machine-learning features that occur after the product is on the market.

- Stricter Definition of Defect – Safety and AI Considerations:

A product is defective if it does not provide the safety one is entitled to expect. However, the assessment of defectiveness now must consider factors like the product’s cybersecurity robustness and compliance with other safety regulations. Notably, “continuous learning” AI products that change after sale can be deemed defective if they develop harmful behavior unexpectedly. Manufacturers are liable for such AI-driven evolution if it was within their control (e.g. through software updates or training).

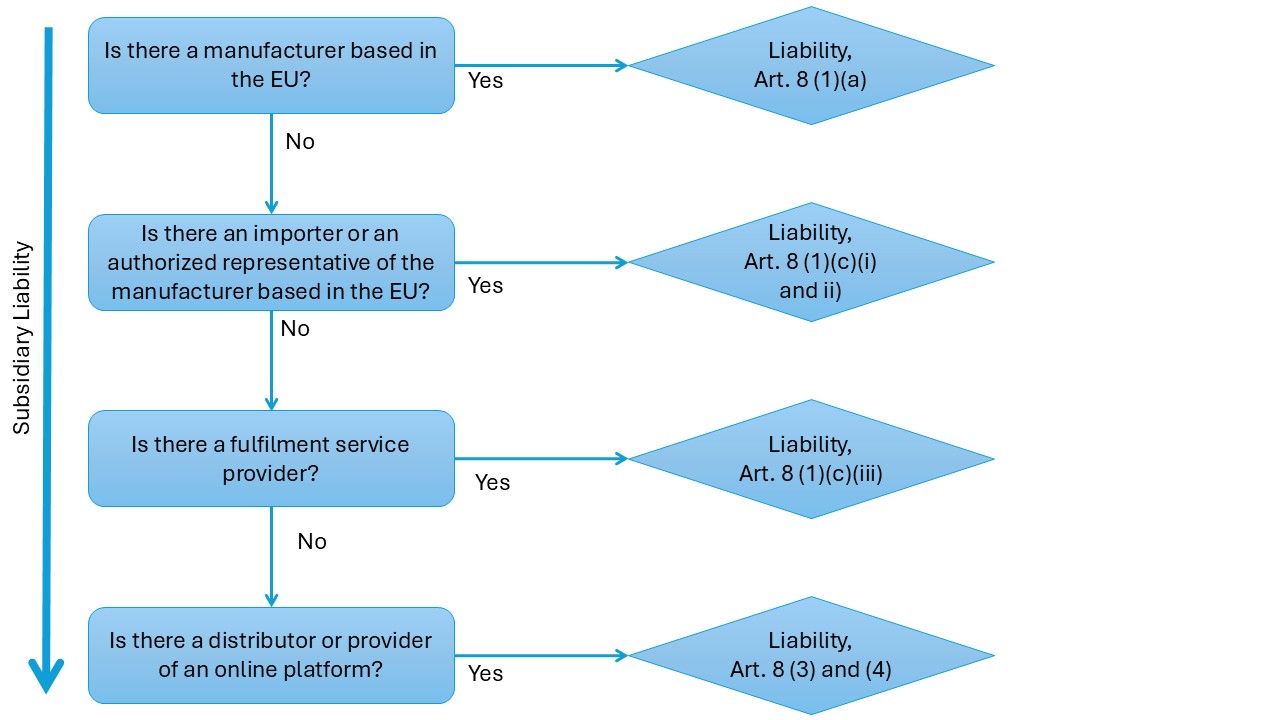

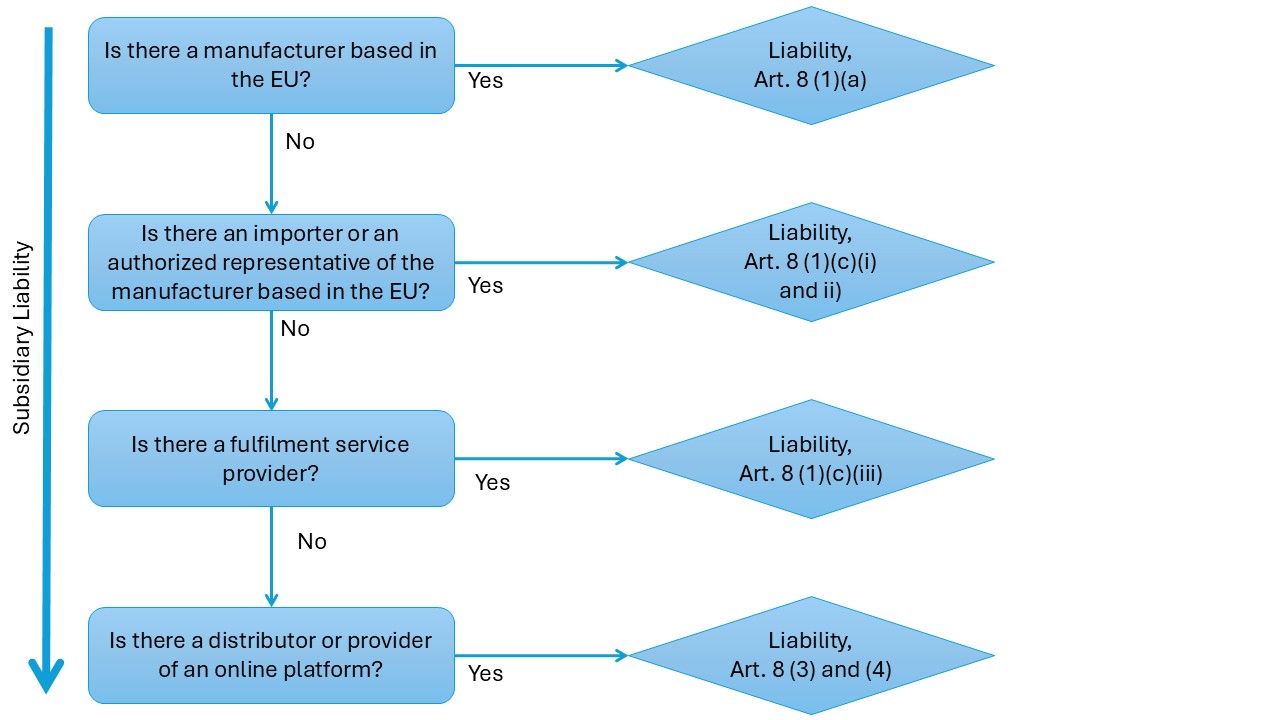

- Expanded Range of Liable Parties:

The PLD ensures there is always an EU-based entity that can be sued for a defective product. In addition to manufacturers and importers, authorized representatives, fulfilment service providers, and in some cases distributors and online marketplaces can be held liable. Those who substantially modify a product or present themselves as its producer (e.g., by rebranding) are also deemed manufacturers under the law.

- Easier Burden of Proof for Claimants:

To tackle the evidentiary challenges of complex products (like AI-enabled devices), the new directive introduces procedural tools to alleviate the burden of proof on consumers. Courts can order manufacturers to disclose relevant evidence once a claimant makes a plausible case. If certain conditions are met, such as the manufacturer failing to cooperate with disclosure, a violation of safety regulations, a malfunction, or extreme technical complexity, courts may presume the product was defective and/or that it caused the damage, sparing the claimant from full proof. These presumptions amount to a partial reversal of the burden of evidence in favor of injured persons.

- Broader Range of Recoverable Damages:

The PLD expands compensable harm to include destruction or corruption of data and related economic loss. For example, if a defective medical device’s software bug wipes out patient data or if a cybersecurity vulnerability in the product enables a hack causing data loss, those losses are recoverable. The directive continues to cover traditional damage categories like personal injury (including psychological harm) and property damage. Purely non-material harms (e.g., violation of privacy or discrimination by an AI output) are not covered under the PLD itself, except to the extent national laws allow some non-material damage claims.

- Removal of Liability Caps and Thresholds:

Under the old rules, manufacturers benefited from certain limitations (a EUR 500 property damage deductible and sometimes national caps on total liability). The new PLD eliminates these limits, exposing companies to uncapped liability for defective products. Even small defects can now lead to claims without any monetary threshold, and there is no upper ceiling on damages a court may award.

- Extended Liability Period (Long-Stop):

The period during which a manufacturer can be held liable after a product is put into circulation has been extended for long-tail harms. The general 10-year long-stop deadline remains, but for cases of latent personal injuries that emerge slowly (especially relevant in healthcare), the deadline is extended up to 25 years. This change acknowledges that some medical device injuries or complications (e.g., from implants or long-term device use) might only become apparent well after a decade.

- Alignment with Other Regulations:

Compliance with other EU product regulations has become even more crucial. A product’s failure to meet mandatory safety requirements under laws like the Medical Devices Regulation (MDR), the proposed AI Act, or the Cyber Resilience Act can be used as evidence of defectiveness. Conversely, maintaining strong compliance and safety standards can help manufacturers defend against liability. The PLD’s changes also dovetail with an upcoming AI Liability Directive (still in development) intended to ease further claimants’ access to evidence in AI-related harm cases.

Digital Products, Software, and AI: An Expanded Scope of “Products”

One of the most transformative updates in the new PLD is the explicit inclusion of digital elements as “products” under product liability law. Previously, it was uncertain in some jurisdictions whether standalone software or AI could be considered a product. The 2024 directive removes this doubt: software of all kinds (applications, operating systems, firmware, etc.) and AI systems are squarely within scope. This holds whether they are sold as independent software or integrated into physical goods (for instance, an AI-driven diagnostic software in a medical imaging device). Even digital files that guide product manufacturing, such as CAD files for 3D printing, are included as products if they can cause damage through their use. (Notably, non-commercial open-source software provided outside of a business activity is excluded, but once software is part of a commercial product or service, it falls under the PLD.

For medical technology companies, this broadened scope is critical. Many modern medical devices rely on software – from MRI machines running complex code to wearable health gadgets with mobile apps, and even purely digital health products like diagnostic AI software. Under the new rules, if a software update in a medical device introduces a bug that causes patient harm, or if an AI algorithm in a diagnostic tool produces a dangerous error due to a flaw, these are treated as product defects just like a physical fault. The manufacturer (or relevant liable party) cannot escape liability by arguing that “software isn’t a product” – the law explicitly says it is.

Importantly, the PLD covers defects that become apparent after the product’s release, including those arising from software updates, upgrades, or machine-learning self-improvement. This means manufacturers remain responsible for the ongoing digital aspects of their products. For example, if a medical device receives a firmware upgrade that later leads to a malfunction, or if an AI-driven insulin pump “learns” in a way that causes it to overdose a patient, the company may be liable for resulting damage. Continuous-learning AI systems are specifically acknowledged: if an AI component continues to evolve in the field, the point in time when the product left the manufacturer’s control doesn’t freeze the product’s state forever. Courts will consider the product’s behavior over time, and if it develops unsafe features later (and the manufacturer had a role in that development, such as providing the AI model or updates), liability can still attach.

The inclusion of “related services” further broadens what manufacturers must account for. If a product relies on a digital service to function (say, a cloud-based analytic service for a medical device that processes patient data), and a defect in that service causes harm, it is treated akin to a product defect. Medical device makers often provide or rely on connected software platforms (for telemedicine, data analytics, etc.); under the PLD, failures in those connected services could lead to strict liability claims against the device manufacturer or service provider.

In summary, the digital expansion of the product concept means medical device companies must treat software and AI components with the same rigor as any physical component when it comes to safety and liability. The entire product ecosystem – device hardware, embedded or accompanying software, and connected digital services – falls under the umbrella of product liability. Manufacturers should therefore ensure robust development and testing practices for software, maintain quality control over updates, and consider liability implications of AI behaviors throughout the product lifecycle.

Defectiveness Redefined: Safety Expectations, AI Behavior, and Cybersecurity

While the fundamental definition of a “defective” product remains – a product is defective when it fails to provide the level of safety that the public is entitled to expect – the new PLD refines the factors to judge safety in light of modern technology. Traditional considerations like the product’s design, instructions, warnings, and the foreseeability of misuse still apply. However, new considerations must be factored in, especially for high-tech products:

- Behavior of AI and Software Over Time:

If a product incorporates AI that can learn or evolve, the law recognizes that its safety must be assessed not only at the moment of sale but also as it changes. A device that was safe at launch could become unsafe later due to how its AI adapts or how its software is updated. The directive explicitly states that products (notably AI systems) that acquire new functions or behaviors post-release can be found defective if those changes lead to harm. Manufacturers are expected to anticipate and manage risks from such “autonomous” or evolving behavior. In practice, this may require robust post-market monitoring of AI performance and possibly setting boundaries on AI self-learning to ensure safety. If an AI-equipped medical device behaves unpredictably and injures a patient, a court may deem it defective and hold the provider liable, unless the provider can prove the product was not at fault – a challenging task given AI opacity.

- Cybersecurity as a Safety Element:

The PLD breaks new ground by treating cybersecurity vulnerabilities as potential defects. If inadequate cybersecurity in a product leaves it open to hacks or data breaches that cause damage, the manufacturer can be liable for those consequences. For instance, if a networked insulin pump or pacemaker has weak security and is compromised by a cyberattack, causing harm to a patient or loss of medical data, that would likely be viewed as a product defect under the new rules. Manufacturers now have a direct liability incentive to build strong cybersecurity features and promptly patch known vulnerabilities – security is no longer just a regulatory or reputational concern, but also a product liability mandate. This dovetails with the proposed EU Cyber Resilience Act, which will impose cybersecurity requirements on device manufacturers; non-compliance with such requirements would weigh against the manufacturer in a PLD claim.

- Compliance with Regulations and Standards:

The expected level of safety is now explicitly linked with compliance with other applicable safety rules. If a product fails to meet mandatory safety requirements set out in EU or national law, that failure can indicate defectiveness. For medical devices, this means that non-compliance with the EU Medical Device Regulation (MDR) or failing to meet harmonized standards could not only lead to regulatory penalties but also civil liability. A regulatory recall or safety notice on a device, for example, would strongly suggest the device was defective in a PLD lawsuit. (While the directive stops short of automatically presuming a defect from regulatory non-compliance, it directs courts to consider such factors.) On the flip side, evidence that a manufacturer adhered to state-of-the-art standards, complied with the MDR, followed relevant codes of conduct, or even the forthcoming AI Act requirements, can help demonstrate that the company took appropriate measures for safety. In essence, regulatory compliance is now intertwined with liability – safety lapses can double expose a company to both regulatory actions and damage claims.

- “State of the Art” and Development Risks:

The new PLD narrows the so-called development risks exemption. Under the old directive, manufacturers in some countries could avoid liability if they proved a risk was scientifically unknowable at the time (the “state of the art” defense). The revised directive allows Member States to derogate from that defense, effectively letting countries bar it and hold manufacturers liable even for unknown risks. This is particularly pertinent for pharmaceutical and medical device makers, as some Member States (like Germany) have already disallowed the development risk defense for medicines. Now there is an EU-level encouragement to limit that defense. Medical device companies should be aware that they might be liable for novel risks their products posed, even if those risks were not discoverable at launch – underscoring the need for continuous update and vigilance as science evolves.

Overall, the concept of a defect now encompasses the high-tech context of products. If a medical device fails due to a software glitch, weak security, or malfunctioning AI logic, it can be deemed defective. The “safety expectation” is measured against current technological and regulatory standards – meaning manufacturers must keep their products updated, secure, and compliant throughout their lifecycle. Proactively, medical device firms should invest in by-design safety, including cybersecurity by design and AI ethics by design, and maintain rigorous post-market surveillance to catch and fix emerging defects (software updates, patches, algorithm improvements) before they cause harm.

Expanded Liability to More Economic Operators and Third Parties

Under the traditional regime, the primary liable party for a defective product is the manufacturer, and if they are not EU-based, the importer who brought the product into the EU would be on the hook. The new PLD significantly broadens the range of potential defendants, reflecting modern supply chains and e-commerce models. The goal is to ensure that an injured person can always find an EU-domiciled entity to sue for compensation. Key extensions include:

- Authorized Representatives:

Many medical device manufacturers outside the EU appoint an EU-based Authorized Representative (AR) under the MDR. The new directive makes it clear that such reps can be held liable as if they were the manufacturer. If a foreign medical device maker has no local presence beyond an AR, an injured patient can sue the AR for a defect. This raises the stakes for ARs – they will likely demand stronger diligence and indemnification from the actual manufacturers they represent, since they now carry direct risk.

- Fulfilment Service Providers:

Companies that provide logistics services (warehousing, packaging, shipping) for products, such as e-commerce fulfillment centers, are now potentially liable for defects if there is no other EU entity (manufacturer, importer, AR) present. For example, if an overseas company sells a medical device directly into the EU via an online platform and uses a fulfillment center in the EU to deliver it, that fulfillment provider could be sued for damages if the device is defective. The PLD defines fulfilment service providers as those professionally offering at least two of these services: warehousing, packaging, addressing, or dispatching, for products they don’t own. They are essentially backstop defendants to cover gaps in the supply chain.

- Distributors as Last-Resort Defendants:

Distributors (wholesalers or retailers) generally were not liable under the old regime unless they failed to identify the producer. The new rules preserve a similar concept: a distributor can be held liable if no other liable party in the EU can be identified. The injured person must first request the distributor to identify who supplied the product or who the manufacturer/importer is; if the distributor doesn’t provide an EU party within one month, the distributor becomes liable. This incentivizes distributors to keep thorough records of their supply chain (something medical device distributors should already do for traceability). It also means in practice that someone in the chain (importer, AR, fulfilment provider, or failing all those, the distributor) will be answerable in the EU for any defective product sold.

The booming role of online platforms in product sales is addressed. If an online marketplace (like an e-commerce platform) plays a role that goes beyond a mere intermediary – for instance, if it presents the product as if it’s its own or exerts a degree of control that a consumer might think the platform is the seller – it can be treated as a liable economic operator. Even when acting as a pure intermediary, a marketplace has obligations under the Digital Services Act (DSA) to assist with identifying manufacturers. If they fail to meet those DSA obligations in the context of a defective product case, they can be held liable similarly to a distributor. In short, online platforms are not completely off the hook and must be careful if they blur the line between marketplace and seller. (For example, if a platform stocks and ships products under its branding or fails to identify a foreign seller clearly, it may find itself facing liability for a defective product).

- Component and Raw Material Suppliers:

Although the directive’s main target is the end-product manufacturer, it also covers component manufacturers in the chain. If a component (hardware or software component) is defective and causes damage, the component’s producer can be directly liable to the injured party, not just the final assembler. This is not new per se, but remains an important point – for instance, if a third-party library used in a medical device’s software is defective, the patient might sue the device maker, who in turn could have recourse against the software library supplier. The PLD makes clear that anyone who designs or produces a product or has their name or brand on it is considered a manufacturer – that includes quasi-manufacturers who brand white-label products as their own.

- Parties Making Substantial Modifications:

A notable addition is that if someone substantially modifies a product post-market, they can become liable as a new manufacturer. A substantial modification could be, for example, refurbishing or remanufacturing a medical device, or significantly altering its software or intended use, outside the original manufacturer’s control. The person or company doing such modifications is then treated as the manufacturer of the “new” product in liability terms. This is especially relevant in the context of the circular economy – companies that recondition used medical equipment or provide third-party software updates/upgrades to devices must recognize that they inherit liability for the outcomes. Medical device remanufacturers will need robust quality controls, since they can’t simply point back to the original manufacturer if something goes wrong after their modifications.

For medical device companies, these expansions mean liability risk is shared (and sometimes shifted) across the supply and distribution network. Non-EU manufacturers must work closely with their EU reps and importers to ensure product safety, as those partners are now directly in the firing line and will demand assurance. E-commerce sales of devices will require careful compliance with platform regulations and possibly setting up an EU presence to avoid burdening a distributor or fulfillment partner with liability. The liability web is wider – everyone touching the product in its journey to the consumer, up to a point, bears some responsibility not to introduce defects and to help trace the source of a defect.

Easing Claimants’ Burden: Disclosure and Presumptions of Defect/Causation

Perhaps the most claimant-friendly innovations in the new directive are the provisions that address the information asymmetry and technical complexity often faced by injured persons. High-tech products like medical devices or AI-driven systems can be “black boxes” to consumers, making it unfairly difficult to prove exactly what went wrong. The PLD tackles this by both forcing more evidence into the open and by softening the burden of proof when strict proof is impractical.

1. Court-ordered Disclosure of Evidence:

Under the new rules, if an injured person can put forward a plausible claim that a product caused damage, courts can require the defendant (e.g., the manufacturer) to disclose relevant evidence in its possession. This is a breakthrough in jurisdictions that don’t have U.S.-style discovery. For example, a patient harmed by a smart infusion pump might allege a software defect but lack access to the device’s internal logs or design specifications. Now the court can compel the manufacturer to provide technical documents, test data, maintenance logs, etc., that are pertinent to the claim. There are safeguards – courts must keep trade secrets or other confidential info protected during this process – but the core idea is to level the playing field. The onus is on manufacturers to be transparent about what might have gone wrong, rather than hiding behind proprietary knowledge. Companies should prepare for this by maintaining good documentation and perhaps creating “explainable” records of how complex algorithms work, in case they need to be shared in litigation.

2. Presumptions Easing Proof:

The directive enumerates several scenarios where the court will presume a defect or causation, shifting the effective burden to the defendant to rebut the presumption. These presumptions dramatically improve a claimant’s chances, especially in cases of complex products:

· Presumption of Defectiveness:

If the manufacturer fails to comply with a disclosure order (withholding or not having evidence), the court can presume the product was defective. Likewise, if the claimant shows the product breached mandatory safety requirements designed to prevent the harm in question, or shows an “obvious malfunction” occurred during normal use, the product is presumed defective. An obvious malfunction could be, say, a pacemaker that stops during normal operation or a surgical robot making an erratic movement – even if the exact technical fault isn’t pinpointed, the malfunction speaks for itself. These rules put strong pressure on manufacturers: comply and prove diligence, or face a default assumption that your product had a defect.

· Presumption of Causation:

If a defect is proven (or presumed) and the resulting damage is of a kind consistent with that defect, the causal link between defect and damage is presumed. For instance, if a defect in a sterilization machine leads to contamination, and a patient develops an infection consistent with that contamination, the court can assume the defect caused the injury without further proof. This spares the victim from having to prove the causal chain scientifically, which can be very complex in medical cases.

· Presumption in Case of Excessive Difficulty (Complex Products):

Perhaps most striking, if an injured person faces excessive difficulty in proving defect or causation due to technical or scientific complexity, and if it’s at least plausible that the product was defective or caused the harm, the court may presume defect and/or causation. This is explicitly aimed at scenarios like AI algorithms, pharmaceuticals, or innovative medical devices, where the science is so complex that a layperson (or even experts) can’t conclusively isolate the defect. Recital 48 of the directive even cites innovative medical devices as an example where this might apply. Essentially, if you have a very complex medical technology and something likely went wrong with it to cause harm, the court can cut through the uncertainty and presume the company is liable – unless the company can prove otherwise. This is a significant shift, as it reverses the traditional burden in hard cases: the manufacturer might have to prove the product was not defective or did not cause the injury, which is notoriously hard to do (proving a negative in a highly complex system).

Together, these measures mean that medical device manufacturers will face a much more claimant-friendly courtroom if their products injure people. For example, a lawsuit over an AI-powered diagnostic device that gave a dangerously wrong result. The patient will be able to obtain internal records about how the AI was trained and how it functions. If the manufacturer refuses or drags its feet, the court may presume the device was defective. Even with information, the patient might not pinpoint where the algorithm erred – but if the case is complex enough, the court can presume a defect as long as the patient shows the scenario is likely one. The manufacturer would then have to prove that the AI was reliable and not the cause of harm, to avoid liability – a reversal of roles compared to the past. This effectively “establish[es] a sort of reversal of the burden of proof” in difficult product cases, forcing producers to exonerate their products.

Medical device companies should therefore prepare for greater transparency and forensic scrutiny of their products. It is advisable to document design decisions, risk assessments, testing, and quality control results, and even to maintain a level of “explainability” for AI algorithms used in devices (e.g., keeping records of algorithm logic or at least a way to interpret outputs). Also, companies should strengthen internal incident investigations – if something goes wrong in the field, promptly gather and preserve evidence (device logs, etc.), because in a future lawsuit, you may need to produce that evidence to avoid a presumption against you. The new landscape effectively rewards manufacturers who are forthright and well-documented, and penalizes those who are opaque or careless with evidence.

Broader Damages and Extended Deadlines for Claims

The 2024 PLD not only simplifies the claims process but also expands the scope of what can be claimed, while providing more time for specific claims to be brought. For medical device manufacturers, this means potentially greater financial exposure per claim and a longer “tail” of liability to worry about.

Expanded Compensable Damages: Under the new directive, victims can be compensated for:

(a) personal injury (including life, limb, or health – and this implicitly covers resulting pain and suffering per national law);

(b) damage to property, and now

(c) loss or corruption of data.

The inclusion of data as a form of property damage is new. In a medical context, consider a defective health app or device that wipes out or corrupts patient health records – the costs to restore that data (or losses caused by its destruction) can be claimed. The directive specifies that financial losses resulting from data being destroyed or corrupted are recoverable, and even the cost of data recovery efforts can be reimbursed if actually incurred (though if data can be restored for free, say from a backup, that particular cost isn’t awarded). This change recognizes that in the digital age, data can be as critical as physical property. Medical providers or patients who lose important medical data due to a device defect might seek compensation for the reconstruction of those records or any harm caused by their loss.

On the other hand, the PLD stops short of covering purely non-economic, non-physical harms that some advanced technologies could inflict. It expressly excludes liability for “pure” privacy infringements or discrimination caused by a product. For example, if an AI in a medical device makes a biased decision that doesn’t physically injure the patient but perhaps violates their dignity or rights, that alone isn’t compensable under PLD (though other laws like GDPR or anti-discrimination laws could apply separately). Similarly, psychological harm is only compensated if it qualifies as personal injury under national law – many countries do allow mental injury connected to physical injury, but not distress in the absence of any physical impact. The takeaway is that PLD remains focused on tangible harm (bodily, property, and now data as a form of property). Any broader notions of harm from AI (like an AI making a harmful decision that doesn’t manifest in physical injury) were left to other legal instruments or a potential future framework. (The EU had proposed an AI Liability Directive to handle some of these intangible harms by easing proof requirements, but as of 2025, that proposal was withdrawn and may be replaced by a future initiative on software liability.)

No Financial Caps or Deductibles: The new directive removes two manufacturer-friendly limits that existed before. First, the old EUR 500 deductible for property damage (meaning a claimant had to suffer over 500 Euros of property loss to claim) is gone. Now, even small property damages are actionable – for instance, if a defective surgical tool damages a €200 piece of equipment, that loss could be claimed, whereas previously it might not have met the threshold. Second, any national caps on total liability (for instance, some countries had an upper ceiling for liability from a batch of pharmaceuticals) are abolished. Liability is unlimited in monetary terms. For a worst-case scenario, consider a wide-scale defect (imagine a software flaw in a radiology device used EU-wide that causes many patients harm) – the manufacturer could face aggregated claims running into tens or hundreds of millions, with no cap per the directive. This calls for manufacturers to reassess their insurance coverage and risk management, as discussed later.

Extended Long-Stop Period (10 to 15/25 Years): Product liability claims in the EU are subject to a “long-stop” – an absolute deadline after which no claim can be brought, regardless of when the victim discovered the damage. The old directive set this at 10 years from the product being put into circulation. The new PLD extends this period in certain cases. Generally, an economic operator remains liable for 10 years, but if the case involves latent personal injury that is slow to emerge, the long-stop is extended to 25 years. The text mentions explicitly health-related harm that takes longer to appear. This is particularly relevant to medical devices: for instance, if someone receives an implant and 15 years later a defect in that implant causes complications, previously they might have been time-barred after 10 years, but now they could still bring a claim within 25 years. Recital 58 of the directive cites that the 25-year extension is to accommodate cases where symptoms are slow to surface – think of things like implant degradation, long-term effects of device materials, or latent software errors that only trigger much later. It’s worth noting that the discoverability rule (usually, victims have 3 years from when they knew or should have known of the damage and defect to file a suit) still applies, but it is bounded by these long-stop periods (whichever is applicable).

For medical device manufacturers, this extension means product liability exposure lasts far longer. Companies must keep records and design history files well beyond a decade – potentially a quarter century – to be able to defend old products if litigation arises. It also has insurance implications: occurrence-based liability policies need to account for the extended claim window, and if coverage is claims-made, insurers and insureds will have to consider how to handle very long-tail claims. Notably, this 25-year long-stop aligns with certain statutes of repose already in some national laws for healthcare products, but now it will be an EU-wide standard for latent injuries.

In sum, the PLD’s changes on damages and time limits broaden the potential impact of each product defect. Medical device firms should anticipate that even minor data-related incidents can lead to claims, that the financial stakes of a mass defect could be higher without caps, and that the responsibility for their products extends for many years into the future. Robust post-market surveillance and maintenance of documentation are key to managing these risks.

Strategies for Compliance and Risk Mitigation

Facing this new landscape, medical device manufacturers (and all producers of high-tech products) should proactively adapt to ensure compliance and to mitigate liability risks. Below are recommendations and strategies:

- Ensure Regulatory Compliance and Safety-by-Design:

First and foremost, meet all applicable safety regulations and standards for your product. Under the PLD, non-compliance with regulations (like MDR, IVDR for diagnostics, or the upcoming AI Act and Cyber Resilience Act) can directly undermine your defense by indicating a defect. Conduct thorough risk assessments and integrate safety measures from the early design stage (“safety by design” and “security by design”). For devices incorporating AI, consider an ethics and bias assessment too – even if AI-caused discrimination isn’t compensable under PLD, a biased AI could still lead to indirect harm or reputational damage. Proactively comply with cybersecurity requirements by implementing strong data encryption, access controls, and a process to address vulnerabilities, as cyber weaknesses can now trigger liability. Compliance isn’t just for passing regulatory audits; it’s now a vital shield in liability cases.

- Robust Post-Market Surveillance and Updates:

Given that defects can arise from software updates or evolving AI, manufacturers must actively monitor their products in the field. Set up systems to collect and analyze feedback, incident reports, and real-world performance data (this aligns with MDR requirements for Post-Market Surveillance and Vigilance). When issues are identified, address them promptly – e.g., issue software patches or safety notices. Keeping products updated is double-edged: failing to provide a needed safety update could be seen as a defect (omission), but providing an update that introduces a defect also incurs liability. Thus, quality control of updates is paramount. Maintain careful version control and testing for any software or firmware releases. Document these activities to show diligence. If an AI in your device is learning continuously, you might consider periodic model reviews or resets to ensure it hasn’t “learned” something dangerous. Essentially, treat the post-launch phase as part of the product’s lifecycle under your responsibility.

- Improve Product Documentation and Transparency:

The new evidence disclosure rules mean you should assume that your internal documents might one day be scrutinized in court. Therefore, keep clear documentation of design decisions, safety margins, and testing. Write technical documents in a comprehensible manner where possible – you might even prepare summary explanations of complex algorithms or mechanisms, in case a court orders you to present information “in an accessible and understandable manner”. This doesn’t mean revealing trade secrets publicly, but it does mean you should be prepared to explain your product’s functioning to non-experts if needed. Develop an internal protocol for handling disclosure requests – e.g., identifying what documentation would be relevant and how to provide it without exposing unnecessary intellectual property. Being forthright and organized can prevent adverse presumptions; if you cooperate with a court order, you avoid the presumption of defect for withholding evidence.

- Revisit Contracts with Supply Chain Partners:

With liability extended to authorized reps, importers, distributors, and fulfilment partners, expect those partners to seek contractual protections. Manufacturers should update agreements to clarify responsibilities for product safety and to include indemnification clauses where appropriate. For instance, an EU Authorized Representative might require the non-EU manufacturer to indemnify them for any PLD claims, and to inform them of any potential safety issues promptly. Distributors may ask for assurance that products comply with all safety standards (since a violation could lead to a defect presumption). Manufacturers, in turn, should ensure that upstream suppliers (component makers, software developers) are contractually obligated to deliver safe components and to share information if issues arise. Also, if you’re selling via an online marketplace or using a fulfillment service, understand their terms and ensure compliance (e.g., providing necessary product information) so that they are not unknowingly put in a liable role. Clear traceability through the supply chain (as required by MDR) is crucial so that in any incident, the responsible entity can be quickly identified – this can protect distributors from becoming default defendants.

- Strengthen Incident Response and Legal Readiness:

In the event of a serious incident or a potential defect coming to light, how you respond can impact subsequent liability. Have a product crisis management plan: this might include steps like promptly informing regulators (to fulfill legal duties and possibly mitigate the regulatory non-compliance argument), issuing recalls or field safety notices when warranted (demonstrating responsibility), and preserving evidence from affected products. Engage experts to investigate and document the root cause of failures – such investigation reports could be invaluable if you need to prove in court that a defect was caused by something outside your control, or conversely, to quickly confirm and fix a defect across all units. Internally, be mindful that communications about product issues could later be disclosable; involve legal counsel early so that investigations are protected under privilege where possible. Essentially, be ready to show that when a problem arose, you did everything that could be expected of a responsible manufacturer.

- Insurance and Liability Coverage:

It is vital to review and likely upgrade your insurance coverage in light of the PLD changes. Ensure your product liability insurance covers not just bodily injury and property damage, but also the new category of data loss claims. Determine whether cybersecurity incidents are covered or if a separate cyber insurance policy is required for scenarios where a hack causes harm. Since liability caps are removed, consider discussing higher coverage limits or aggregate limits with insurers. The extended claim period (up to 25 years for some injuries) means you may need to adjust how long you maintain coverage for products no longer sold – possibly tail coverage provisions. Insurers themselves will be adapting to this new risk environment (they are aware that claims may rise with these claimant-friendly rules), so work closely to find the right coverage and premiums for your risk profile.

Culture of safety and compliance within your organization. Front-line engineers, designers, and product managers should be made aware that their work can have serious liability implications years down the line. Provide training on the importance of documentation, of adhering to standards, and of designing with not just regulatory approval in mind but also worst-case product liability scenarios. For example, if incorporating an AI module, the team should consider: how would we explain this AI’s decision process to a court if something goes wrong? If you foster an internal mindset that “if it’s not documented, it didn’t happen; and if it’s not safe, it will cost us,” you align your workforce with the company’s risk management goals. Engaging quality and regulatory experts early in design and throughout development is key – something medtech firms likely do under MDR, but now even the legal team might want a seat at the table to foresee liability issues.

By taking these steps, manufacturers can not only reduce the risk of defects and ensuing claims but also put themselves in a far better position to defend against any claims that do arise under the new PLD regime. The directive ultimately seeks to balance innovation with accountability – companies that are diligent and transparent will find that they can still innovate, while those that cut corners on safety may face greater exposure.

Conclusion

The EU’s new Product Liability Directive (2024/2853) represents a significant shift in the product liability landscape, particularly for tech-driven sectors like medical devices. It brings previously gray areas – software, AI, data loss, cybersecurity – into the liability framework clearly, ensuring that injured people can seek compensation even in the era of digital products and complex technologies. It also tilts the scales toward claimants by addressing information gaps and easing the proof burden in appropriate cases. At the same time, it spreads responsibility across the supply chain, reflecting that in a global market, multiple actors influence a product’s safety.

For medical device manufacturers, who operate at the intersection of cutting-edge innovation and human safety, these changes are both a warning and an opportunity. The warning is that legal exposure is higher than before – defects can lead to bigger and longer-tail liabilities, and any weakness in your product’s safety (be it a software bug or a compliance lapse) could more readily become a successful claim against you. The opportunity, however, is that by embracing the spirit of these changes – doubling down on safety, transparency, and robust design – manufacturers can build greater trust in their products. In an environment where patients and healthcare providers may be wary of AI and new tech, knowing that there’s a strong liability recourse if something goes wrong can actually encourage adoption of innovative products. In that sense, the PLD aims to “ensure claimants enjoy the same level of protection irrespective of the technology involved”, which in turn supports the uptake of new technologies by assuring a fair balance of risks.

The directive is fully in force as of December 2024, but EU Member States have until 9 December 2026 to transpose it into national laws. This means companies have a short grace period to prepare. Products placed on the market before that date will still fall under the old rules, but anything launched from late 2026 onward will live under the new regime. Given product development cycles, any new medical device in the pipeline now will likely be sold under the PLD’s tenure – so there’s no time to lose in updating your practices.

In conclusion, the new PLD brings product liability into the 21st century, with all the associated challenges of AI, software, and global commerce. Medical device manufacturers should view compliance with it not merely as a legal checkbox, but as an integral part of delivering safe and effective innovations in healthcare. By reinforcing their commitment to quality and being prepared for greater accountability, companies can continue to innovate confidently, knowing they have also safeguarded their business and patients to the highest degree possible under the new law.